Proportional representation might appear to cure Bangladesh’s winner-take-all distortions, yet in a patronage-soaked, institutionally weak democracy it would almost certainly

parliament into quarrelling factions, paralyze policymaking, and invite both foreign meddling and military “rescues.” Until the country fortifies its electoral bodies and culture of governance, switching to PR would be less a democratic upgrade than a high-risk transplant on an ailing patient.

Proportional representation (PR) is an electoral system where a party’s share of parliamentary seats reflects its share of the popular vote, unlike Bangladesh’s first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, where candidates can win with 30-40% of votes. PR ensures seats match vote shares, reducing “wasted” votes and distortions where a party wins 70-80% of seats with 40% of votes. After disputed elections and one-party rule, civic groups and minor parties, including Jamaat-e-Islami, support PR for fairer, multi-party representation.

Advocates claim PR would curb muscle power, black money, and nomination trading, create a level electoral playing field, and ensure that Islamist and other minority voices gain seats alongside major parties, preventing any single winner from steamrolling the opposition. It sounds like a democratic dream come true. But in practice, it could easily become Bangladesh’s worst nightmare.

Fragmentation and Weak Governments: A Recipe for Paralysis

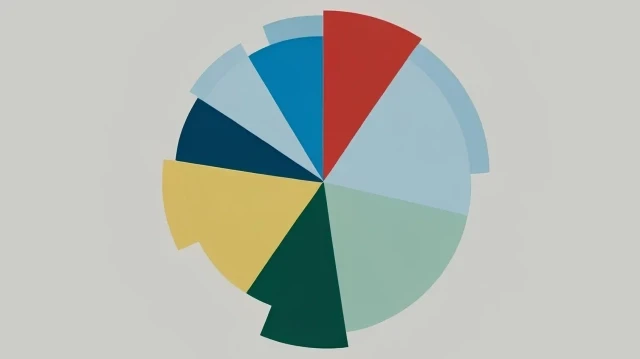

The flip side of proportional representation’s inclusivity is political fragmentation. By making it easier for smaller parties (even fringe and single-issue groups) to win seats, PR virtually guarantees a fractured parliament with many factions – and no single party anywhere near a majority. PR is the perfect vehicle through which the managerial state becomes even less decisive and political—in the truest sense of the word. Comparative

bears this out: worldwide, FPTP systems average about 2.5 effective political parties, while PR systems average around 4.5 – nearly double the

. Inevitably, this means coalition governments would become the norm. Between 2000 and 2017, only 23% of elections in plurality systems (like FPTP) led to coalitions, compared to a whopping 87% under PR

. In other words, if Bangladesh switches to PR, it is almost certain that every future government will be a multi party coalition cobbled together after the vote. And that is where the trouble begins. A higher frequency of coalition governments increases unpredictability regarding which parties will form them.

Coalition governments might sound conducive to “unity,” but in reality more coalition governments mean more unstable governments. A coalition is a marriage of convenience forged by post-election bargaining – deals struck not by voters but by party elites negotiating cabinet posts and pet projects. This process often takes weeks if not months; on average,

found that PR countries take about 50 days to form a government after an election (vs ~32 days even in mixed systems).

For example, the Netherlands (PR) often takes 2–3 months (e.g., 225 days in 2017), while Germany (mixed system) averages 30–50 days (e.g., 54 days in 2013, 171 days in 2017). Belgium infamously went 541 days without a government in 2010-2011 because its PR-elected parties could not agree on a coalition.

Do we really believe Bangladesh would fare any better? It struggled to even hold timely, uncontested elections; imagine the added chaos of an election yielding a hung parliament and then protracted haggling as rival party bosses barter for power. As one Bangladesh country risk

noted, there is a very real possibility a PR-based election here would result in a hung parliament, leading to long-term political instability. This is definitely the last thing that foreign and domestic investors want for their businesses. Add to this the academic

that PR systems, due to coalition governments, are associated with higher public spending and deficits, as parties negotiate budget concessions to maintain coalitions, undermining economic stability. The specter of parliamentary deadlock looms large in the absence of consensus on the electoral system itself – and that

would only worsen after a PR election produces no clear winner. Governing would require appeasing numerous small parties—many ideologically narrow—so every bill could be

by one disgruntled faction. With five or six parties constantly bargaining instead of two broad coalitions compromising internally, legislation would slow, horse-trading would dominate, and fragile governments could collapse over minor disputes.

In a young democracy like Bangladesh, where trust in politicians is already low, this would breed further disillusionment – everyone can claim credit, but no one accepts blame and responsibility.

Worse still, a fragmented coalition government in Bangladesh would likely be weak and indecisive, precisely at a time when strong decisions are needed for a true democratic and

transition. The country is facing economic and security gusts that demand coherent policy responses. Yet coalition governments notoriously struggle to pursue bold

; every policy must be watered down to appease multiple partners.

For Bangladesh, adopting PR could lead to paralysis on critical issues like infrastructure, financial stability, and security. PR almost always leads to quick government turnovers before completing the intended term, which will require frequent expensive elections. Nepal’s

with coalition politics serves as a warning: nine governments in eight years, delayed constitution finalization by seven years, and stalled economic growth due to constant infighting, party splits, and unstable alliances. This led to high unemployment, youth emigration, and investor withdrawal. This is the nightmare that proportional representation could bring to Bangladesh: serial governments that rise and fall before they can govern, and a policy agenda held hostage by every junior coalition partner’s whims.

Indeed, even far more institutionalized democracies have buckled under the strain of fragmented PR politics. Look at Italy and Israel, often cited as examples of PR’s pitfalls: both have suffered chronic instability due to excessive coalition fragmentation. These are societies with robust economies and state institutions; Bangladesh’s institutions are considerably more fragile, meaning the effects of constant coalition instability could be even more dire.

Institutions, Political Culture, & Geopolitics : Is Bangladesh Ready for PR?

Beyond the arithmetic of coalition politics, one must ask: is Bangladesh institutionally prepared to make PR work? Democracy is more than electoral formulas; it relies on a culture of compromise, strong neutral institutions, and public trust in the system. On all these fronts, Bangladesh today falls woefully short. It is naïve to think a mere change of voting system to PR would overnight transform these deeply entrenched shortages.

Proportional representation replaces local candidates with party lists, making MPs beholden to party bosses rather than constituents. In Bangladesh’s patronage-heavy politics, this weakens accountability and intensifies loyalty to a central leadership clique, fostering sycophancy. Seats could go to big donors or loyalists, shifting corruption from constituency vote-buying to jockeying for high list positions. Thus, PR risks trading today’s flaws for deeper internal party control and new forms of favoritism.

Under FPTP every locality, despite flaws, still has a dedicated MP responsible for its needs. Proportional representation assigns MPs to nationwide party vote blocs, so no one is clearly accountable for a remote village or district. In a country already grappling with weak accountability, such diluted ties between representatives and constituents could further erode effective local advocacy.

A Coalition fragility under PR could leave Bangladesh vulnerable to foreign manipulation and domestic military intervention. A hung parliament in Dhaka would invite external powers— Western democracies pressing for process, regional rivals offering loans—to back their preferred factions, eroding sovereignty. Persistent gridlock might also tempt the armed forces to step in “to restore order,” replacing elected leaders with a caretaker technocracy or outright coup. Thus, a voting system meant to deepen democracy could instead weaken the state and open the way for authoritarian actors.

Not a Cure-All, But a Pandora’s Box

Bangladesh’s policy elites should heed regional experience and academic research: proportional representation may promise broader participation, but it risks crippling political stability and governance. Instead of rushing into a full PR system, focus on incremental fixes—fortify the Election Commission, guarantee impartial caretakers, and nurture respect for democratic norms. Introducing pure PR into today’s polarized, fragile democracy would be like a heart transplant in a feverish patient: poor timing, low odds of success. Stronger institutions—not a new electoral formula—are the real cure.

is a Lecturer at the Lewis Honors College at the University of Kentucky, specializing in international relations with a focus on the peace science tradition. His research and teaching interests include the causes of war and peace—frequently examined through the lens of popular culture—as well as international security in Asia and foreign policy.

*The views in this article belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect Yeni Şafak's editorial policy.